Selecting VR Therapy Content

Before a client uses virtual reality as part of treatment, the therapist must select appropriate content or review their prior content selection based on the client's treatment plan. This tutorial explains the practical issues involved in content selection for each content usage, including both in-session VR and client homework.

Selecting content is a different process from selecting VR therapy products or supporting content. We suggest reading this guide before reading the VR Therapy Technology Overview, VR Therapy Products Buyer's Guide, or the VR Therapy Supporting Content Buyer's Guide.

Sources of VR Content

Most of the VR content used in therapy will be provided by a VR therapy product that enables the therapist to monitor and control the client's experience using a therapist workstation. Workstation controls allow the therapist to select content, start or stop content interaction or video, and modify aspects of the client's virtual experience.

Content from other sources (aka "supporting content") may also be used during therapy or as client homework. Content from these sources do not offer similar therapist controls. For example, consumer VR apps, 3-D videos from You Tube, non-VR consumer apps for self-help or skills training, etc.

Content to support VR therapy can be viewed as a series of content modules which can be used for one or more therapeutic purposes, as explained below. Content module is a general term covering all types of content including a specific virtual environment or scene, a 3-D video, 3-D still image, or other image types.

Each VR product provides one or more content modules. Most VR therapy products include all the content needed to treat one or more mental health conditions, but some products only include content for exposure therapy and not skills training or reward/relaxation. Some vendors offer certain content modules as part of multiple VR therapy products, where each product addresses a different group of conditions. For example, the same relaxation skills training modules may be offered as part of several products for treating fears and phobias, along with fear-specific exposure content.

A therapist may use VR content from multiple sources at different times during a client’s treatment to achieve specific treatment goals. This may include one or more VR therapy products and supporting content.

For example, treatment for fear of flying might include:

-

Skills training for diaphragmatic breathing using pre-recorded instructions for belly breathing accompanied by a relaxing virtual environment. These instructions could be part of a VR therapy app or a consumer VR app.

-

Exposure therapy using virtual environments that depict an airport gate area and check-in counter, boarding the airplane via the jetway, and sitting on the plane during boarding, taxiing, takeoff, flight, and landing. Using a VR therapy product for these VEs allows the therapist to monitor and control aspects of the client's in-flight experience including changing the time of day, weather conditions, and turbulence while flying.

-

Reward and relaxation enjoying a 3-D video of a tropical beach scene from a VR therapy app or a consumer VR app.

-

Homework practicing diaphragmatic breathing using a consumer meditation app that encourages and tracks daily practice.

Ways to Use VR Content

VR content can be used for different purposes during therapy. Uses of VR include:

-

Diagnosis or differential diagnosis.

-

Instructional materials for skills training and practice.

-

Exposure therapy using VR or augmented reality (AR).

-

Rewards, relaxation, or reinforcement.

-

Relapse prevention.

-

Homework between sessions.

-

'Other' uses of VR. For example, a VR tool for use during eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy to provide visual or auditory stimuli.

Note that the SVRT VR Therapy Product Buyer's Guide includes content for Skills Training, Exposure, Reward/Relaxation, Homework, and Other. Look under Exposure for content that can be used for diagnosis or relapse prevention.

Selecting Content for Diagnosis

Diagnosis confirmation or differential diagnosis generally uses exposure therapy content related to the diagnosis being considered or ruled out. For example, to see if a client being treated for fear of flying also fears being in an enclosed space, the therapist might place the client in a small room virtual environment that is part of a VR therapy product intended for use in treating claustrophobia.

Selecting Content for Skills Training

When selecting skills training content, the therapist should decide what skills they would like the client to develop as part of the client's treatment plan, assess the client's current skill level (if any), and determine what type of instruction will be most effective for each client. This may involve some trial and error.

Psychoeducation may also be useful for helping clients understand their condition or symptoms. Some VR therapy products include VR psychoeducational content related to the conditions they address. Supporting content for psychoeducation is available in VR or many other formats.

One advantage of providing instructional material in VR is that the VR headset helps clients focus on the content by blocking out potential distractions.

VR instructional materials can combine audio instructions for therapeutic skills training with explanatory visuals or relaxing virtual environments. For example, the client may listen to instructions for diaphragmatic breathing, mindfulness meditation, or progressive muscle relaxation while watching a virtual coach demonstrate the skill or in a relaxing VE.

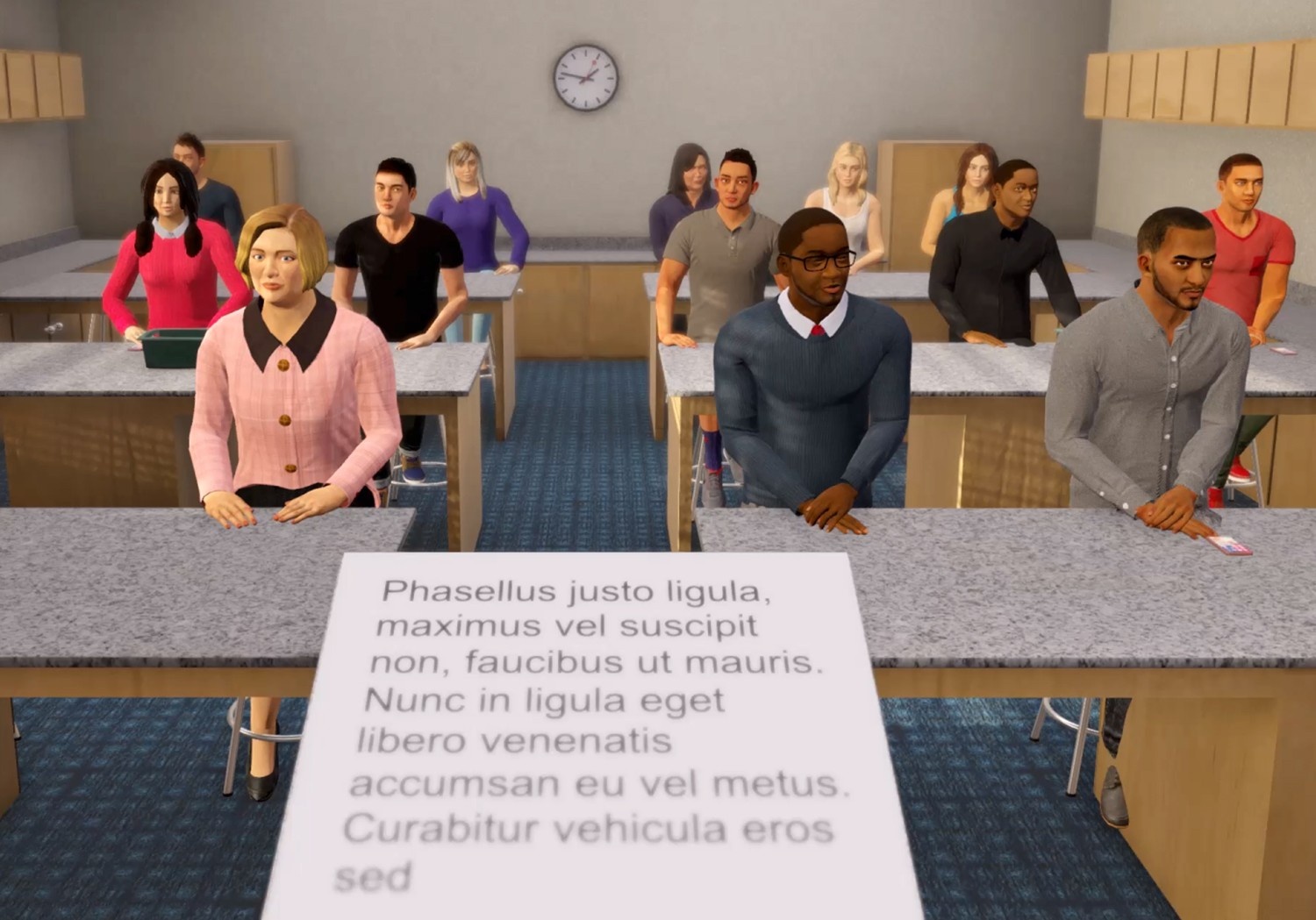

Figure: Example VR Instructional Material Scene (VBI)

Recorded instructions can also help clients practice coping skills during other activities. For example, while a client is experiencing a stressful virtual environment, their therapist can play audio instructions for coping skills and coach them to improve their ability to apply these skills under pressure.

Although consumer skills training apps do not support therapist monitoring, these apps can be useful for helping clients learn skills, establish regular habits, and practice at home between sessions. For example, a mindfulness app may encourage daily meditation practice, or an insomnia app can teach sleep strategies, provide tools for keeping sleep records, and help identify sleep issues. Options include consumer VR apps, non-VR apps for smartphones or smartwatches, wired fitness devices (such as Mirror, Peloton, etc.), and online programs or classes.

When selecting instructional content for a client, the therapist should consider:

-

What specific skills or other information would you like each client to learn? For example, an anxiety client may need diaphragmatic breathing as a coping skill and basic psychoeducation regarding anxiety symptom safety.

-

Is the instructional style suitable for each client's age/education, language and cultural preferences, other values, etc.?

-

Describing any “relaxing” VE or other visual imagery to the client and confirm that the client will find the imagery relaxing, before immersing them in the environment. For example, a beach scene may be very relaxing for many clients, but too exposed for an agoraphobic client, or linked to unpleasant personal memories for another client.

-

If you want a client to practice skills at home or independently, check that the VR product or app is compatible with the client's devices.

Selecting Content for VR Exposure Therapy

Virtual environments can provide experiences that resemble each client’s anxiety-provoking activities or situations. Exposure therapy includes systematically having clients experience and master a series of progressively more challenging activities or situations.

When planning exposure therapy, a therapist will typically create an exposure hierarchy for each client, based the client’s report of how much fear is triggered by different activities or situations. An exposure hierarchy lists specific situations or activities, sensations, and/or thoughts the client finds progressively more frightening and factors that increase or decrease their fear.

To learn more about exposure therapy, and how to create an exposure hierarchy, see Virtual Reality Therapy for Anxiety: A Guide for Therapists (McMahon, 2022, Routledge.com).

Content for each virtual experience can be selected by the therapist and tailored using therapist workstation controls to evoke more or less anxiety, based on the client’s exposure hierarchy. Virtual experiences may include audio or other sensory stimuli, in addition to visual content.

For example:

-

Fear of Driving may include VEs of driving on city streets, freeways, bridges, tunnels, etc. The therapist may control aspects of the client experience including time of day, weather conditions, traffic density, number of passengers in the car, etc.

-

Fear of Flying may include VEs for the taxi ride to the airport, waiting at the gate, boarding the airplane, take off, in-flight conditions, landing, etc. The therapist may control aspects of the client experience including seat position, time of day, weather conditions, turbulence, in-flight announcements, etc.

-

Fear of Heights may include VEs for solid or glass elevators, balconies, open atriums, etc. The therapist may control aspects of the client experience including elevator type, number of people in the elevator, floor level, distance from the edge, etc.

Issues to consider when selecting content for exposure include:

-

Find VR content relevant to the client's specific fear, even if the VR content is not labeled as being designed to treat that fear. For example, a small elevator VE designed for treating fear of heights may also be useful for treating claustrophobia, generalized anxiety disorder, or other fears.

-

Aim to evoke a therapeutically 'just right' level of fear associated with each activity or situation. The evoked response should neither be too much (risking increasing the client’s fear and damaging the therapeutic relationship) or too little to be effective.

-

Watch out for fear cross contamination issues because many clients have more than one fear. For example, if you are treating someone for fear of heights, and you don't know that they also have claustrophobia, you may be surprised by their reaction to entering the small elevator VE.

When selecting content for exposure, VR therapy products are the preferred source of content because these products allow the therapist to monitor the client's experience and control certain aspects of the client's experience using a therapist workstation.

Content from other sources may be useful in therapy for situations where suitable content that matches a client's feared activities or situations is not available in a VR therapy product. This may include VR content from other sources, non-VR content that can be viewed in a headset, or other types of content.

For example:

-

Fears linked to a specific geographic location, such as PTSD associated with an assault, might be treated using Google Street View to provide 3-D images of the actual building where the event occurred.

-

Fear of heights that is specific to ski lifts may be treated using videos of ski-lifts since current VR therapy products for fear of heights do not include ski lift content.

-

Fear of driving over one specific bridge may be treated with videos of that bridge.

-

Fear of tropical insects of unusual size (not spiders or roaches) may be treated using videos or photos of similar looking insects.

Images that appear in virtual environments may be created or recorded using several different technologies. The image type or source can affect the amount of detail or realism, the ability to control movement within the VE, and options for therapist controls that modify aspects of the client's experience.

VEs are created using these types of images, individually or in combinations:

-

Computer-generated imagery (CGI) visuals are created using software models, somewhat like computer-aided design (CAD) systems. Models can be based on actual locations or objects that are captured using 3-D scanners, but small details and textures may be left out, so the resulting image looks more like a cartoon than a movie.

-

3-D videos filmed using a special camera and showing real-life activities, situations, and people are generally more detailed and realistic looking than CGI images. One limitation of a VR video is that it is pre-recorded, and the therapist has little or no ability to change what happens or the point of view.

-

3-D still images taken using a 3-D camera or captured from a 3-D video. For clients who are unusually fearful, avoidant, or distress intolerant, VR photos may provide the lowest level of VR exposure; another benefit is that VR photos do not trigger nausea because there is no motion.

-

Augmented reality (AR) combines CGI objects with live video from a camera. AR content may be viewed on a smartphone (similar to Pokémon Go), tablet, using an AR headset, or special AR glasses.

Figure: Example CGI VE Scene (BehaVR)

Figure: Example 3-D Video VE Scene (BehaVR/Limbix)

Figure: Example 3-D Photo VE Scene (BehaVR/Limbix)

Figure: AR Spider Example (Phobos)

The types of images used to create a VE influences how realistic the environment appears to be, the user's ability to navigate within an environment, how much control the therapist may have over contents, and the appearance of the environment, objects, and people. CGI people are called avatars.

Realism

3-D videos and still images are most realistic looking because they can include fine details and textures. CGI models used for VR therapy products (as contrasted to movie special effects) are typically simple animations and may incorporate generic-looking visual elements. CGI people, or avatars, may look cartoon-like and the same, or very similar looking, avatars may appear in multiple VEs.

Augmented reality superimposes CGI objects onto a scene. These objects are generally cartoon-like in appearance.

Navigation

Options for the user to move around within a virtual environment, and what the user can see, also vary depending on the type of image used:

-

CGI models allow the user to move around or look almost anywhere within a VE, although if the user ventures away from the typical pathway they may see things that do not make sense. For example, a CGI airplane interior may appear normal while looking to the right or left (including out the window), but if you look down you might see an empty seat and floor where you would expect to see your body.

-

3-D videos are filmed from a specific point of view which may be stationary or move along a fixed path. For example, in a driving video the user can look forward or off to one side, but the camera always follows the same path along the road.

-

3-D stills have a fixed point of view. The user may be able to look around, but the camera location is fixed.

-

Augmented reality images can be superimposed on different locations by moving the camera around. The superimposed figures may appear more realistic when viewed on a horizontal surface.

Therapist Controls

The type or source of the images used in a virtual environment determine the extent to which a therapist can control or modify the client's experience using the therapist workstation. Specifically:

-

CGI content provides the most flexibility and therapist controls may include multiple options for modifying the virtual environment or changing aspects of the user's experience. For example, in a VE for public speaking anxiety the therapist may be able to change the type of room, the number of audience members, audience age, gender, and appearance options, or select animation routines that trigger audience behaviors and comments.

-

3-D video content is pre-recorded so the overall action sequence is fixed, although the therapist may be able to start, pause, or rewind the video; pausing the video may show a freeze-frame or a black screen. Some videos include superimposed CGI effects that provide therapist controls over the time of day or weather.

-

3-D stills are static and do not provide any therapist controls.

-

Augmented reality provides therapist controls over the size, number, and activity of the CGI animated figures superimposed on the image viewed through the camera.

People and Avatars

People are represented differently in virtual environments, depending on the type of images:

-

CGI content may include “people” that are computer-generated animated human figures, also known as avatars.

-

3-D videos are recordings that show actual people doing things in real situations.

-

3-D stills are immersive photographs of actual people and places.

For a CGI virtual environment, the therapist controls may include specifying the avatar options such as age, gender, hairstyles, clothing, and other appearance options. Avatar options in VR therapy products are becoming more inclusive, but in many cases the only options are Anglo, cisgender, and able bodied.

A client may or may not have their own avatar within a CGI VE. In a VE where the user does have an avatar, they may get to select a self-image from a library of alternatives for gender, hair style, clothing, etc. This choice of self-image/avatar can be important part of the client experience in certain applications of VR. For example, trying out an avatar with different age, gender, ethnicity, or sexual orientation as part of diversity training.

Composite VEs

Just like movie special effects that superimpose live actors on a CGI background, a VE may combine images from two or more sources in different ways. Hybrid virtual environments can combine 3-D video or images of actual locations or objects with CGI objects, videos, or photos.

For example, the driving VE shown in the figure below combines a CGI automobile interior with 3-D video of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway 101 visible through the car windows. Therapist controls for this VE provide the ability to change the time of day by using CGI effects to darken the sky or change the weather by adding CGI raindrops and windshield wipers. The resulting images are very evocative, even though some of the details may look peculiar.

Figure: Composite VE Example (BehaVR/Limbix)

Augmented Reality

Augmented reality combines live video with computer-generated images that are superimposed onto objects shown in the video. AR images may be viewable on a smartphone (using the phone camera), a tablet computer, a combination VR/AR headset that incorporates a camera, or special AR glasses that include a camera and the ability to superimpose display content on scenes viewed through the lenses.

One application of this technology is smartphone app for insect phobia exposure that superimposes insects onto a scene viewed using the smartphone camera and display. Therapist controls can adjust the number of insects, their size, and movements.

Figure: AR Spider Example (Phobos)

Selecting Reward/Relaxation Content

Soothing virtual environments or games can be used as rewards or relaxation during VR therapy. Example virtual environments for this purpose include beach scenes, meadows, underwater scenes, etc. It can be particularly beneficial to end a session by rewarding the client with a pleasant virtual experience.

Issues to consider when selecting content for reward/relaxation include:

-

Compatibility with the client's preferences and issues. For example, a client with claustrophobia may not be comfortable underwater, or a client with agoraphobia may not find wide open spaces rewarding.

-

Checking with the client for their personal issues and comfort level before introducing a new VE. For example, tropical beach scenes may trigger unhappy memories of past events and lost relationships based on a client's personal history.

Figure: Example Reward/Relaxation VE (Psious)

Selecting Relapse Prevention Content

Relapse Prevention generally uses the same VR contents as exposure therapy for the condition being treated. The therapist may increase the exposure intensity, or make challenging statements, in an effort to provoke a fear response in order to demonstrate to the client that they are no longer frightened by this activity or situation.

Selecting Homework Content

Client homework can focus on several different areas, depending on what is being addressed in therapy. For anxiety treatment, homework may include using VR for:

-

Instructional material for skills building or psychoeducation. Options for instructional materials, including use for homework, were discussed above.

-

Exposure therapy practice of facing feared activities or situations while practicing coping skills and revised thought patterns.

Issues to consider when selecting content for VR exposure homework include:

-

Has the client progressed far enough to be ready for home practice?

-

Does home content reflect same client issues and fears as other exposure?

-

Can the client control the content well enough to practice without becoming overwhelmed or traumatized?

Options for home VR exposure content include:

-

VR therapy products used in-session (especially for teletherapy) if the product can be used without a therapist workstation.

-

Consumer VR apps.

-

VR content from You Tube or other sources.

In general, clients should be advised not to search the Internet for VR content that could be used for exposure. Online videos are not intended for therapeutic use or screened to avoid potential harm. Many videos have been staged or edited to provoke very intense reactions. This may be fine for thrill-seekers without anxiety, panic, phobias, trauma history, etc. but these videos can easily be counter-therapeutic and sensitizing for anxiety clients. Be selective about which videos you recommend for use during therapy or as homework.

Anxiety treatment may also involve homework that does not involve VR. See Virtual Reality Therapy for Anxiety: A Guide for Therapists (McMahon, 2022, Routledge.com) and the forms, records, and exercises in the associated client workbook Overcoming Anxiety and Panic interactive guide (McMahon, 2019, Hands-on-Guide, www.overcoming.guide).

Next Steps

See the VR Therapy Technology Overview, a tutorial intended to help a therapist figure out what resources they need for adding VR to their practice.